I’m not a geek, exactly, but I do have a keen interest in digital technology, especially its impact on our attitudes and activities. An iphone is the only Apple product I own; my desktop is a PC, my laptop is a Razer, and my tablet is a Kindle Fire. I spread the wealth, so to speak.

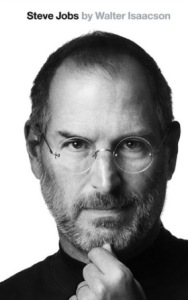

Even so, my admiration for Apple products has recently grown. It began shortly after reading Laura Sydell’s article, “New Film Asks: Were Steve Jobs’ Flaws Uploaded To His Machines?” (NPR).* Her article led me to Walter Isaacson’s very fine, authorized biography, Steve Jobs (2011), which I’m about halfway through.

Isaacson takes a no-holds-barred approach to chronicling Jobs’ life. In fact, as the book’s publisher explains, not only did Jobs cooperate with the author, “he asked for no control over what was written. He put nothing off-limits.” Although the book clearly reveals his character flaws and professional missteps, Jobs’ brilliance as a designer and showman – and his enormous influence on how we think about and interact with digital technology (including film animation: think Pixar) – shines through.

Jobs’ design philosophy – Simplicity – is what intrigues me the most. His chief designer, Jonathan (Jony) Ive, shared Jobs’ belief that “less is better” and told Isaacson, “Simplicity isn’t just a visual style. It’s not just minimalism or the absence of clutter. It involves digging through the depth of the complexity. To be truly simple, you have to go really deep.” Isaacson adds, “Design was not just about what a product looked like on the surface. It had to reflect the product’s essence” (342).

What is meant by “the product’s essence” isn’t explicitly discussed, but clues are here and there. For one thing, Jobs kept his focus on the consumer’s experience rather than the company’s bottomline, especially on the ease of use. A related clue is the “i” in front of Apple products; it originally referred to “integrating” devices with the “Internet,” then expanded to include “individuality” and “innovation,” signifying that Apple products are both personal and revolutionary (see Wikipedia iMac history).

The biggest clue as to Apple’s essence, at least so far in my reading, comes in Isaacson’s chapter on the development of the iPod. He says that “the iPod became the essence of everything Apple was destined to be: poetry connected to engineering, arts and creativity intersecting with technology, design that’s bold and simple. It had the ease of use that came from being an integrated end-to-end system, from computer to FireWire to device to software to content management” (393). So we could add “intersection,” “interaction,” and even “interdisciplinary” to the previous iList of meanings.

Jobs’ ease-of-use approach extended to the creation of the Apple stores. For example, Larry Ellison, Oracle CEO, told Isaacson, “If you look at the stores and the products, you will see Steve’s obsession with beauty as simplicity…which goes all the way to the checkout process in the stores…. It means the absolute minimum number of steps. Steve gave us the exact, explicit recipe for how he wanted the checkout to work” (372).

In other words, Jobs respected people’s time. While developing the first Macintosh, for instance, he demanded a faster boot up. Before the engineer could explain why it wasn’t faster, “Jobs went to a whiteboard and showed that if there were five million people using the Mac, and it took ten seconds extra to turn it on every day, that added up to…the equivalent of at least one hundred lifetimes saved per year” (123). Soon the boot up was 28 seconds faster.

Aesthetics and craftsmanship were every bit as important as efficiency to Jobs. Take product packaging. He and Jony Ive spent lots of time on package design. Ive explained why: “You design a ritual of unpacking to make the product feel special. Packaging can be theater, it can create a story.” Isaacson agrees: “Apple customers know the feeling of opening up a well-crafted box and finding the product nestled in an inviting fashion” (347). The sheer elegance and sturdiness of the small white iPhone boxes may be why I saved mine.

Jobs’ passion, Isaacson says, was “for making a great product, not just a profitable one.” Andy Hertzfeld, an engineer on the original Mac team, told Isaacson, “Jobs thought of himself as an artist, and he encouraged our design team to think of ourselves that way too…. The goal was never to beat the competition, or to make a lot of money. It was to do the greatest thing possible, or even a little greater” (123).

Jobs once told Isaacson that “as a kid” he “read something that one of his heroes, Edwin Land Polaroid, said about the importance of people who stand at the intersection of humanities and science, and I decided that’s what I wanted to do” (Introduction). Clearly he succeeded: devices that combine engineering with poetry, packaging with theater, aesthetics with efficiency, elegance with craft, and passion with simplicity.

Got to admire it!

__________________________________________

Notes

*Sydell’s article is about Alex Gibney’s documentary Steve Jobs: The Man in the Machine (trailer), released in September 2015. Danny Boyle’s movie Steve Jobs (trailer) will be released very soon; the screenplay was written by Aaron Sorkin and based on Walter Isaacson’s biography.

*Photos: The book-cover image is the same one that came with my Kindle edition. I took the other photos with my iPhone: iPhone earbuds, paperweight, and iPhone box.

Really enjoyed this essay! In the end, there is much to admire about Steve Jobs.

LikeLike

Thank you for checking out my first post. If you haven’t already, I think you might enjoy reading Isaacson’s biography – many interesting details about his journey, and, in a sense ours, digitally speaking :).

LikeLike